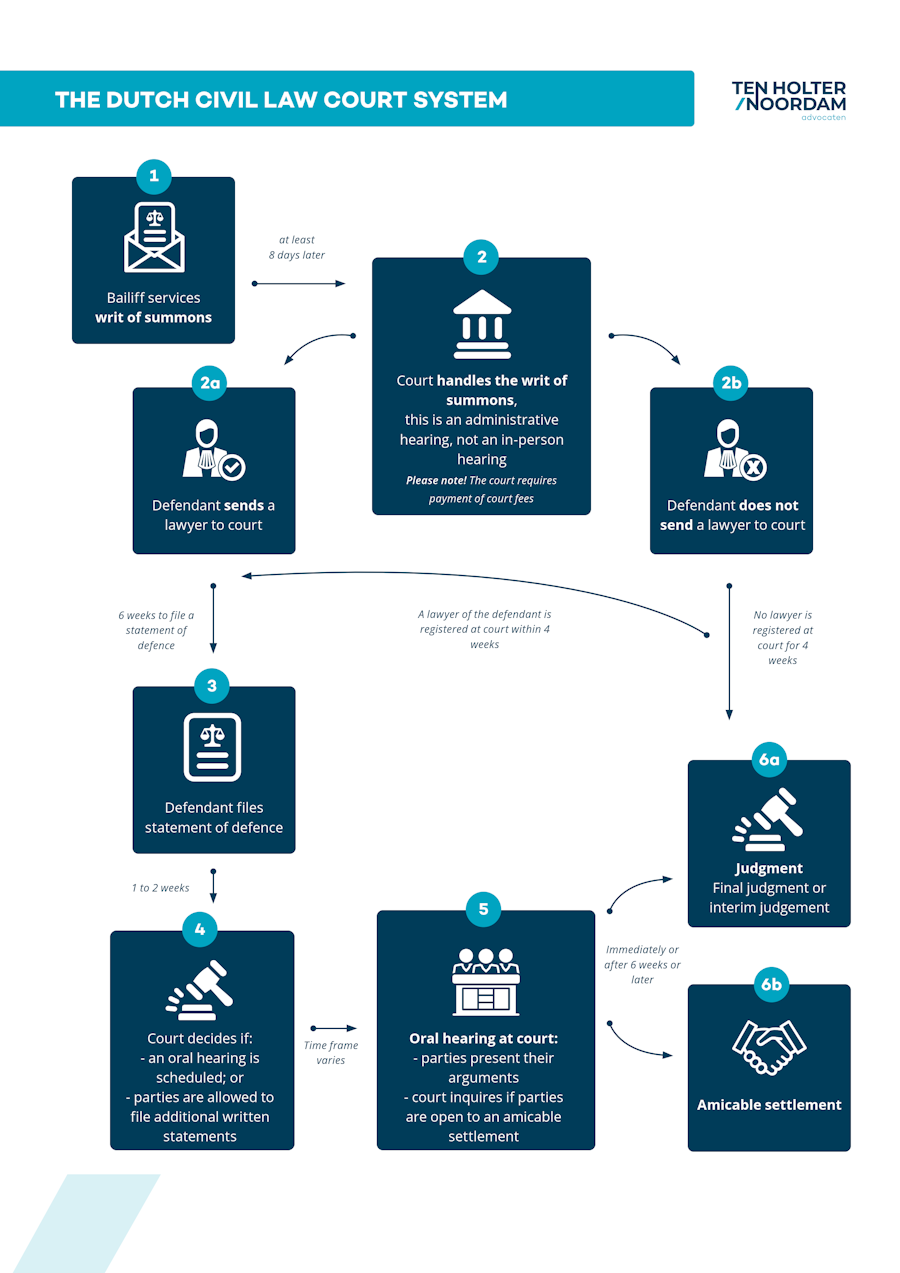

This roadmap illustrates the typical course of a civil court case in the Netherlands. Please click on each step on the left-hand side of this webpage to navigate through the webpage and obtain more detailed information on each step.

Step 1 - Bailiff delivers summons

In order to initiate court proceedings, the claimant - the party who starts the proceedings - must produce a writ of summons (Dutch: dagvaarding). The writ is a summons is a document that calls the recipient (also called defendant or opposing party) to appear in court. In the writ, the claimant states what is going on and sets out what he demands from the counterparty. The claimant must substantiate its case with as much documentary evidence as possible. In order to ensure that the court can trust that the summons has actually been received, it is delivered by a Dutch bailiff.

Step 2 - Court handles the summons

At least 8 days after the bailiff delivered the summons, the court will process the summons. In ordinary civil cases, this takes happens behind the scenes (note: in sub district/cantonal cases, there is also an actual hearing). In general, the court asks all parties that appear to pay court fees, which is an amount of money to handle the case. The amount varies per category of case, but most often it is linked to the sum demanded by the plaintiff. There are two options after this step, dependent on whether a lawyer has come forward for the defendant. See step 2b. and 2b. In 'normal' civil proceedings, it is obligatory to have the assistance of a lawyer. An exception to this rule are cases handled by the subdistrict/cantonal court. These courts decide, among other things, on disputes concerning tenancy law, labour law and claims amounting to less than € 25,000.

Step 2a - Lawyer representing the defendant

If a lawyer has registered on behalf of the defendant at court, the lawyer will have the opportunity to reply to the summons (step 3).

Step 2b - Defendant does not send representation to the court

If the defendant does not send a lawyer to the court, the court will schedule the case to be judged (step 6a - judgement). The standard period for this is four weeks (two weeks at cantonal courts). During this period, the defendant's lawyer can still present itself to court. If this happens, the lawyers will be allowed to reply to the summons. If no lawyer appears, the judge will rule in the absence of the defendant. This is called a 'judgment in absentia'.

Step 3 - Defendant submits its defence

Once a lawyer has come forward for the defendant, the court provides six weeks to reply in writing to the summons. That document is called a 'statement of defence' (Dutch: conclusie van antwoord). In this document, the defendant is allowed to simultaneously submit a counterclaim. Once the court has recieved the statement of defence, the further course of the case is determined at an behind the scenes (administrative) hearing - the so-called roll call (Dutch: rolzitting).

Step 4 - Court decides

At the roll call hearing, a judge decides on the next steps in the proceedings. A hearing on the merits of the case follows later, which is why parties do not need to attend this administrative hearing. The most common decision is that a physical hearing (on the merits of the case) will be scheduled, but it also happens that the parties are allowed to send additional written statements to the court. If that happens, a physical hearing is often scheduled after these statements have been made.

Step 5 - Court hearing

Hearings tend to be an in-person hearing at the court building and deals with the merits of the case. Usually, quite some time - often months - has expired between the court's decision to have a hearing and the actual hearing taking place. At the hearing at least one judge and one court clerk are present. The court clerk takes notes of what is said during the hearing (note: these notes are not verbatim). During the hearing, both parties have the opportunity to argue their points of view (via their lawyer). In addition, the judge asks questions to both parties. Finally, a judge will always inquire if the parties are open to settle at the hearing. This means that two outcomes are possible at a hearing, either the judge issues a judgment or the disputing parties make a deal, known as a settlement, at or shortly after the hearing.

Step 6a - Judgment (final or interim)

The judge may deliver as an oral judgement during the hearing, but this is exceptional. More commonly, the court mails the written decision on the case approximately six weeks after the hearing. The court has the prerogative to postpone this, meaning the judgment will be rendered at a later date. A judgment contains the decision of the judge(s). If the entire dispute was decided, we speak of a final judgement and the proceedings are over. If the court has not ruled on the whole dispute, we speak of an interim or interlocutory judgment. For example, a court can decide in an interlocutory judgment that more evidence must be provided by a party. In such a case, the proceedings will continue after the interlocutory judgment is rendered.

Step 6b – Settlement

At a hearing, the judge will almost always inquire whether the parties are prepared to negotiate a settlement of the dispute. If the parties are open to dialogue, the judge will suspend the hearing so that the participants can negotiate a solution in the hallway of the court. If parties reach a mutual solution, the judge will immediately record the outcome in a written record (Dutch: procesverbaal). This will be signed by both parties and is thus legally binding. That means that the parties are required to comply with the recorded agreement. If there is no settlement, the judge will decide the dispute and the matter will be scheduled for judgment (see step 6a).